Introduction

“Because freedom, I am told, is nothing but the distance between the hunter and its prey.”

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

I’d like to begin by unpacking a title, one that belongs to both the organisation I’m writing for and the institution that exhibits history. The museum, at least in the most palatable understanding of the term, is a repository: a physical archive of historical memory. As a space it facilitates collective witnessing and communal ways of articulating history, the future, place, belonging, and the universe. But as a concept, or a socio-political trajectory, it contains and perpetuates so much violence. Global capitalism locates museums in European centres where they contribute to the economic and cultural capital of these nations despite being built almost entirely on stolen things, stories, and vulnerabilities. More than just a repository then the museum, much like the parliament, the church, or the court of law, takes on the form of an active, almost insidious, agent used by the powers that be to control narratives. How can we begin to dismantle this?

This piece is an ongoing inquiry into dismantling and decentering power and what that looks like at the institutional, community, and individual levels. Power manifests in various forms: we first begin to recognise power in individuals—parents, teachers, leaders of the state—but as we grow conscious we realise that people exist to form dominant structures. Some have secret, intimate understandings of these structures—capitalism, colonialism, democracy, the patriarchy—because they architect them, and over time it becomes abundantly clear that to receive your “lot in life” is fundamentally to deal in power; to groom, tend, tidy, and maintain a status quo that privileges your desires, your safety, your ability to possess more. No sooner do we leave the confines of the womb than we are drawn into the belly of a social order that will never release us—the battle of self versus others in the bid for freedom.

Freedom can mean power. The power to decide who and what you are, independent of what is told, expected, required. It is also the power to decide who and what everyone else is: where they belong, how they work, what they get paid, who they serve, who serves them, what they desire, who they desire, how they dream. But freedom can also mean redistribution. The movement away from citadels of power and into community; undoing hierarchies and state apparatus; investing time and energy in our neighbours and in our soil; rest and joy as resistance. This is freedom for the oppressed, the marginalised, the displaced.

Part I: Locating Violence in Capitalist Democracies

“Which would be the better revenge: to thrive within this system, spiting the people who’d tried to crush you? Or to upend everything, crushing them in turn?”

Jeremy Tiang, State of Emergency

Locating the violence and dispossession inherent in capitalist democracies means that we have to first go on a journey of myth-busting. Power, and the preservation of it, isn’t just dependent on violence; it also leverages greatly on asserting dominant narratives, or, myths. The first big myth we are peddled, which I gleaned from watching the short film Wonderland (2016) by Erkan Özgen, is that geographical borders and boundaries are legitimate. The second, adapted from Jonas Staal’s lecture on Stateless Assembly 1[1]

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/69/60626/ideology-form/, is that we need citizenships for political self-determination. I’m wary of invoking too much Marxist theory, although it is the foundation of almost everything I am saying here, because that is not the tone and structure I am going for. Nevertheless I think it would be valuable to introduce an excerpt from The State and Revolution2[2]

https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch05.htm for context, especially since ‘capitalist democracy’ is a phrase we are going to encounter often.

Democracy for an insignificant minority, democracy for the rich—that is the democracy of capitalist society. If we look more closely into the machinery of capitalist democracy, we see everywhere, in the “petty”—supposedly petty—details of the suffrage (residential qualifications, exclusion of women, etc.), in the technique of the representative institutions, in the actual obstacles to the right of assembly (public buildings are not for “paupers”!), in the purely capitalist organization of the daily press, etc., etc.,—we see restriction after restriction upon democracy. These restrictions, exceptions, exclusions, obstacles for the poor seem slight, especially in the eyes of one who has never known want himself and has never been inclose contact with the oppressed classes in their mass life (and 9 out of 10, if not 99 out of 100, bourgeois publicists and politicians come under this category); but in their sum total these restrictions exclude and squeeze out the poor from politics, from active participation in democracy.

Marx grasped this essence of capitalist democracy splendidly when, in analysing the experience of the Commune, he said that the oppressed are allowed once every few years to decide which particular representatives of the oppressing class shall represent and repress them in parliament!

Wonderland (2016) features a 13-year-old boy named Mohammed whose family fled their town, Kobani, during the Syrian war. Kobani is a small town in Southwestern Kurdistan, presently known as Rojava, that held a 107-day long resistance against ISIS attacks in 2014. Along with 130,000 other people over the course of just 4 days, Mohammed and his family fled across the border to Turkey as refugees—the first of many ‘borders’ I encountered through Mohammed—and were permanently displaced from their homes by no fault of their own. Mohammed is deaf-mute, so he uses only his body to communicate his experiences—the second ‘border’. With just meticulous actions Mohammed narrates an entire war: the absence of water, beheading, books being torn, missiles and so on. The body becomes a medium that universalises language, where language is often predicated on conditions such as voice, translation, speaking, communication.

Mohammed’s story raises the question of borders—geographical borders, material barricades, immaterial boundaries, confines of language—and the pressing need to dismantle them. Refugees are dying, both literally and figuratively, to cross what Kochenov3[3]

D. Kochenov, Citizenship (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2019), 44-51. calls the “preassigned border of opportunity” (49), which are composed of nothing more than man-made divisions of people who choose to abide by the status quo, people who don’t, and people who are caught in the crosshairs. These are divisions installed only to protect capital and to keep people in ‘their place’. To quote Kochenov again, “erecting impenetrable walls shutting out the citizens of the neediest and most poorly governed nations explains why the rubber boats cross the Mediterranean in one direction only” (44).

Borders manifest as citizenship, the next most violent mechanism wielded by capitalist democracies. Citizenship is a tool of global inequality perpetuated by the myth of choice i.e. democracy, and has been used historically to control despite masquerading as something we should be so lucky to have. James Tully locates the inherent friction between citizenship and democracy quite aptly: “The globalisation of modern citizenship has not tended to democracy, equality, independence and peace, as its justificatory theories proclaim, but to informal imperialism, inequality, dependence, and war.”4[4]

J. Tully, On Global Citizenship (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 32. The richest countries open up their borders to one another, offering passports and tickets to a cosmopolitanism that will create more wealth, but watch silently as more than 15,000 people died in the Mediterranean between 2012 and 2017 trying to flee another version of citizenship that happened to afford them poor life chances. Decentering power means demanding self-governance, because citizenship is an instrument of oppression that purports nationalist collectiveness but breeds an individualism where connectedness is only via our strings to the state’s marionettist.

Part II: #smileinsolidarity as Anti-Capitalist Praxis

We were raised in a country whose very foundations lay upon the notion of processing; generations of men whose tread upon this soil was analysed and assessed for risk; liberated from their valuables, and proscribed names to fit into the culture. All for the honour of living upon this blessed land, where exploitation—whether through employment, housing or life expectancy—was simply an honest opportunity that had failed to be realised, through either laziness or ineptitude. We stood in lines all our lives, waiting for our food stamps, to enrol into community college, to plead with our housing boards, to see lawyers or organisations that may have shown even the slightest interest in our case. We stood in lines and waited our turn.

Niven Govinden, This Brutal House

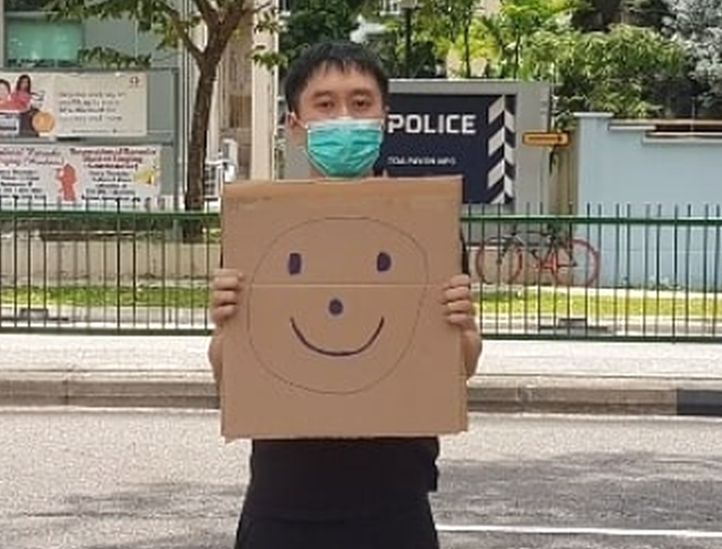

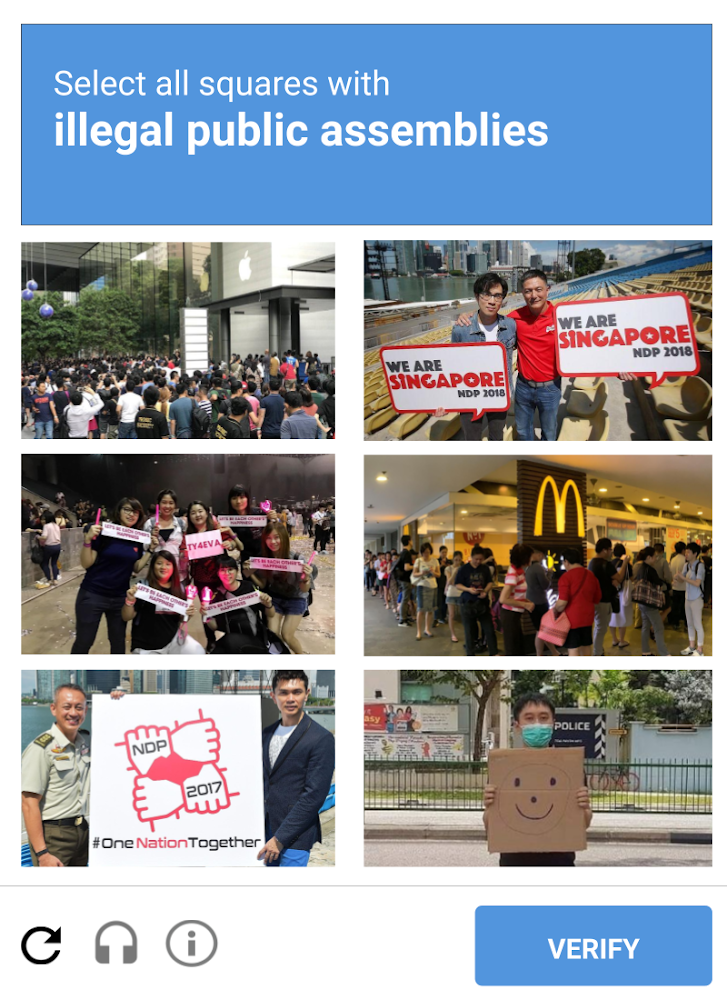

On 28th March 2020, Jolovan Wham held up a smiley face that was wilfully interpreted by the Singaporean state to be a form of illegal or unlawful assembly. Despite having just taken a picture with the face drawn on cardboard, he was charged with violating public order, on the grounds that he carried out a one-man protest.

This was not the first time that the state, under the guise of protecting the social fabric and the nation’s pre-existing peace and security, had made use of legality and policing to silence voices and work that did not echo theirs. But beyond the hypocrisy of curtailing dissent and the violence of policing, there is an absurdity and a fragility to this particular interaction that cannot go unseen: for all its purported glory and strength, the iron fist that justifies its rule with the constant, looming threat of chaos has lost its grip. A fallibility peers out of the now loosened fist which, more than anything, speaks to the fact that it is possible to undermine and destabilise a bureaucratic government body with a single hand drawn smiley face. What does that mean about the democratic state? How do we locate and value the exclusivity of our citizenship within an institutional body that is at once weak enough to be threatened by dissent yet powerful enough to imprison those who use their voice?

This is the inherent hypocrisy present in capitalist democracy—a force that is at once too vulnerable to be lobbied against but at the same time too superior to stand on equal footing with its citizens. It is this same logic (or lack thereof) we are met with as children asking our parents why we cannot have something, only to be told it is “because they say so”: a sweeping, unfounded declaration that doesn’t need to be explained or justified simply because the power hierarchy ordains and power asymmetry excuses. Decentering power means finding an Achilles’ heel and piercing it.

To me, Wham holding up the sign was two things: 1) an important act of solidarity with two young climate activists, Wong J-Min and Ngyuen Nhat Min, who were similarly investigated by the police5[5]

20-year-old Nguyen Nhat Min held up a sign that read “SG is better than oil” in the same spot as Jolovan and 18-year-old Wong J-Min held up messages on pieces of paper that read “PLANET OVER PROFIT”, “SCHOOL STRIKE 4 CLIMATE”, and “ExxonMobil KILLS KITTENS & PUPPIES” outside the ExxonMobil office at Harbourfront., and 2) a defining moment for all other anti- or post-capitalist advocacy to come. Capitalism tells us that spaces don’t belong to people—they belong to corporations, institutions, and the state. As people we have to buy, rent, lease, apply, ballot, and be “approved” to live, work, rest, play, perform, and campaign in these spaces, which make them inherently undemocratic. I cannot set up a lemonade booth outside my house for thirsty passers-by, or sit at a void deck and offer free tuition classes to children from low-income families, or stand by the road with a sign that reads “HOW MANY MIGRANT WORKERS DIED BUILDING THE MARINA BAY SANDS?” without submitting an application, seeking approval, and being granted a permit because my care, my anger, and my existence in community spaces first have to be stamped and approved and deemed non-threatening by the state.

One of the workshops I attended as part of ’s the Museum for the Displaced’s (M fD) Assembly was a Cantastoria workshop by Bread and Puppet Theater. Cantastoria, which comes from the Italian “story-singer”, is theatre that is meant to be fashioned quickly and cheaply using the things around you in order to respond to political events. One of the participants (they wish to remain anonymous) performed a piece which involved reading out a series of ostensibly bureaucratic words and phrases that are used by the state and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) to process requests from low-wage migrant workers in Singapore.

“pending approval”, “we regret to inform you”, “insufficient documentation”, “failure to submit supporting documents”, “duly noted”, “authorised”, “we acknowledge your wait”, “we have reviewed your case” “please refer to your appeal”, “please refer to your re-appeal”, “your case is under consideration”, “need not reply”, “this is an automated response”, “please see below”, “ineligible”, “our records show”

This language isn’t the story. It is a shadow of the story, and importantly the disenfranchisement, that cannot be performed by migrant bodies. It’s the space in between the story.

Perhaps #smileinsolidarity is, in some way, also a form of Cantastoria. The only difference is that Wham’s narrative was performed belatedly and by actors other than himself. The outrage at the hypocrisy inherent in capitalist democracies was exposed by the state themselves, expounded on by the media, and circulated by spectators. Without saying anything at all Wham both echoed the political demands of the two climate activists and occupied space, even if just for a few seconds. I return to that image of Wham very often. There is something in the way his hands grip the sides of a scrap piece of cardboard, against a backdrop so comically Singaporean (the MoBike, the pristine roads, the banners that are careful to include a representative from each dominant racial group) that reminds me how little we have to lay claim to; how little is ours. When the sun sets on this imperialist, capitalist democracy, maybe all we really have is some discarded cardboard and our idea(l)s.

I used the term ‘praxis’ to describe #smileinsolidarity because I believe it has given us both a structure to follow, and a shining example of hypocrisy to lobby under. Decentering power means taking back spaces used by the powers that be to control narratives, be they cultural, political, social, or otherwise. Decentering power means reclaiming spaces and putting them back in the hands of the people. The space occupied by Wham, since immortalised by a picture, will now always be a space of solidarity, permit notwithstanding.

Part III: Migrant Narratives and Empowering People to Tell Stories About Themselves

“Poetry is not only dream and vision; it is the skeleton architecture of our lives. It lays the foundations for a future of change, a bridge across our fears of what has never been before.”

Audre Lorde, Poetry Is Not A Luxury6[6]

First published in Chrysalis: A Magazine of Female Culture, no. 3 (1977).

It only makes sense for me to begin this portion with Lorde because I think her seminal essay, Poetry Is Not A Luxury, perfectly encapsulates the condition of creative work in neoliberal societies, especially when produced by the working class. There is a clear class divide in terms of who is allowed to make art, to partake in the “revelatory distillation of experience” (Lorde, 26). The rich are empowered to be thinkers; to muse, to spend their days writing, to ruminate on theories and conditions of existence. The poor are required to work; to labour for themselves and for others, to produce capital, to keep the gears of the economy oiled and running. We tell ourselves it’s meritocracy, a perfect theory that maintains richness comes from hard work and intelligence while poverty comes from laziness and poor choices, but the myth of the level playing field and intellectual scarcity has historically been told by capitalist wolves in neoliberal sheep’s clothing.

In the 1960s, Singaporeans were told that “poetry is a luxury we cannot afford”7[7]

Lee Kuan Yew (Singapore’s first Prime Minister) to students at the National University of Singapore in 1968., and this has since become the trajectory of our culture: a classic pitting of art and capitalism (or it’s patriotic alias: “economic growth”) as inherently incompatible. I don’t think this is untrue, because art, in many ways and forms, must be anti-capitalist at its core. But the state wasn’t producing socialists—what they wanted us to understand was that we weren’t supposed to sit around and write poetry or make art; we were supposed to work hard, earn money, contribute to the economy, commit to the growth of a nation.

People have been responding creatively to tragedy, circumstance, love, loss, and so on for ages. It is no different for migrant workers, who use poetry as an outlet and, as of late, an alternative source of income. For example, the Migrant Worker Poetry Competition in Singapore was launched by Singaporeans in 2014 to recognise and reward excellent poetry written by migrant workers. I am critical of the competition for various reasons, but critique notwithstanding, I think it has become a significant stage—both physical and metaphorical—for migrant workers to tell stories about themselves, and to correct false, dominant narratives about who they are as a diasporic people. It is a space where once a year, Things Missing From The Migrant Narrative, As Told By The State and Things Present In The Migrant Narrative, As Told By Themselves finally converge in stanzas and rhymes to be ranked, praised, and prized by local literati.

Decentering power means de-linking art, profit, “high culture”, and neoliberalism. Just as Cantastoria democratises art, we must start looking at migrant worker poetry as valid and meaningful beyond the confines of cultural capital, or a competition. People’s struggles are valid and concerning even when they don’t have the language to articulate their oppression. The Migrant Worker Poetry Competition is hosted at and by the National Gallery Singapore, which brings us back to the idea of the museum as a site of violence. Museums are one of the most ostensibly classed spaces in society—its patrons hardly belong to the working class and are almost never migrant workers. To include them in this space, on one day each year, just to pin blue ribbons onto their lapels as a means of distracting from the systemic injustices that plague them every single day is violence. The dispensing of culture for capital (with reference to Lee Kuan Yew’s sentiments above), only to turn it into capital is classic neoliberal gameplay. For the rich this stance is simply symptomatic of a state that ‘cannot appreciate art’ 8[8]

Here it would be valuable for the reader to refer to the ‘are artists essential’ debate that took place on social media in December last year., but for the working class (especially low-wage migrant work), it is a rendering of their bodies within an additional axis of oppression: doubly disenfranchised by both wage labour and artistic expression. Migrant workers are not ‘additionally useful or valuable’ to us because they write poetry; they are valuable because their labour creates the foundation upon which all else is built—homes, families, economies. To eclipse this and all other injustice from the national narrative but hand them cash prizes once a year for speaking the truth in a way that contributes to cultural capital is violence. Decentering power means unpicking the relationship between art and capital; poetry is not a luxury because for some, it is a means of survival.

Below is a poem9[9]

Published in Songs From A Distance, Selected Poems from the 2015 and 2016 Migrant Worker Poetry Competition. Translation is available at the end titled ‘The Labourer’ by Monir Ahmod, who writes under the pseudonym ‘Shromik’, which means Worker. He considers himself a rebel poet.

হে নান্দনিক সভ্যতার কারিগর,

অট্টালিকার ইট থেকে মুছে গেছে

তোমার ঘামের পরশ।

স্যাতস্যাঁতে সিমেন্টের আস্তরে

আজ রঙিন দালান,

বাবুইয়ের মতো কারুকাজ করা শহরে শহরে

তোমার ছবি কখনোই ভাসবে না।

এই বিলাসের সাম্রাজ্যে তুমি উত্তরাধিকারের দুর্ভিক্ষ নিয়েই

বেঁচে রবে গহীন অরণ্যে।

কেউ জানে না তোমারও প্রেম আছে স্বপ্নের ভিতরে স্বপ্ব আছে

দুর্গন্ধের গায়েও চাঁদের পরীরা জোছনা ঢালে মনের মাধুরী দিয়ে।

হে কারিগর এই পৃথিবীর বুক আল্পনা করে

চিরনিদ্রায় শায়িত হবে একদিন।

হয়তো আমিনুলের মত বেওয়ারিশ লাশ হয়ে

পড়ে রবে লেকপাড়ে।

হয়তো রুহুল আমিনের মতো তোমার লাশ মাতৃভূমির মাটি ছোঁয়ার যোগ্যতা হারাবে প্রবাসী

হওয়ার অপরাধে।

রানা প্লাজার ইট-পাথরে ডুবে তাজরীনের আগুনে জ্বলে

হয়তো হারিয়ে যাবে পৃধিবীর গ্রহ থেকে

তোমার রক্ত -ঘাম উপেক্ষা করে

ঝিলমিল করে উঠবে রঙধনুর পৃথিবী।

তোমার সমাধিহীন পৃথিবীর বুকে

স্বর্গবাসীর ডায়েরির পাতায় তুমি ইতিহাস হয়ে রবে, অপাঠ্য ইতিহাস!

How violent is it that people who create the literal framework of culture are removed from having a stake in it? How violent is it that people can be removed in the first place?

Part IV: Imagining Alternative Paradigms to Democracy and Kinship

“It is said that the personal is political. That is not true, of course. At the core of the fight for political rights is the desire to protect ourselves, to prevent the political from intruding on our individual lives. Personal and political are interdependent but not one and the same thing. The realm of imagination is a bridge between them, constantly refashioning one in terms of the other.”

Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran

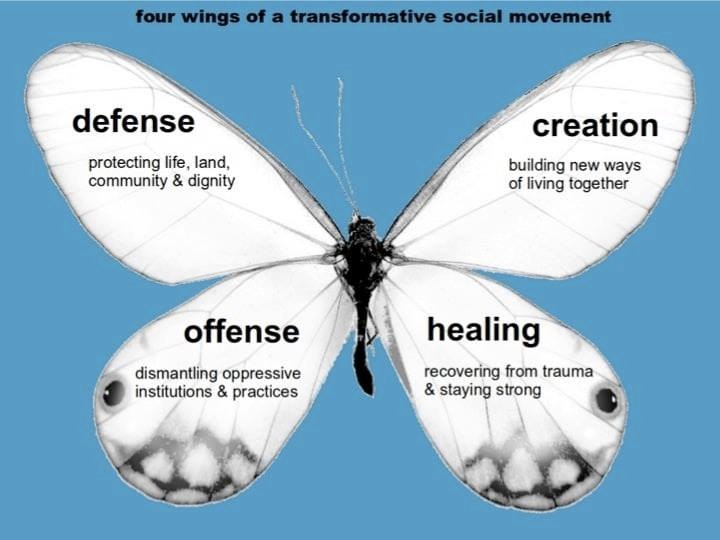

Just thinking about this section captivated me because imagination is such an underrated form of resistance. The imagination isn’t just a bridge between the personal and the political but a series of bridges connecting different paradigms—a network of intersecting alternatives that exist above life as we presently know it; like a pristine spider web spun at the highest corner of a dusty room. Genuine democracy cannot exist without the freedom to imagine; to know our worlds, duties, desires, and refashion them with endless possibility. When I think about transformation, organisation, and alternatives, I think of the ‘Four Wings’, which is a fabric I incorporate into my personal practise as much as possible.

Creation is the most exciting wing, because it is an invitation to explore; to create new existences and ways of relating to one another; to re-imagine history and power; to re-write white man’s theory; to erase binaries and nuclearity; to respect the earth and its favours to us. Decentering power means deliberately building new ways of living together.

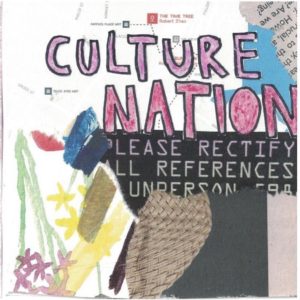

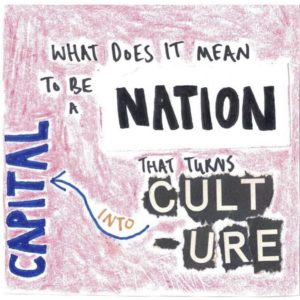

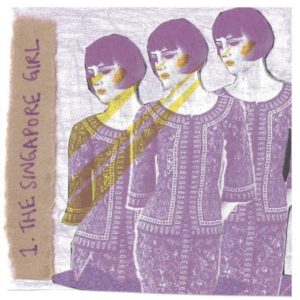

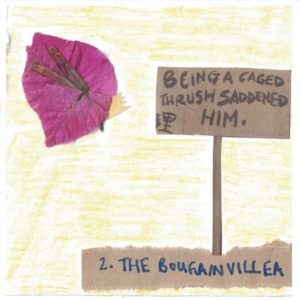

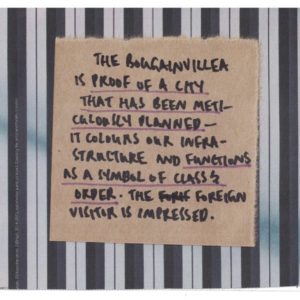

Some time ago I created a piece that expounded on two specific, local emblems of capitalism: the Bougainvillea flower and the Singapore Girl. It was an amateur attempt at a zine and is made up entirely of scrap paper, cut-outs from brochures & magazines, crayons, a brown paper bag, and an actual Bougainvillea flower. I went into the process knowing I wanted to create / not knowing what I wanted to create and the result was a great deal more clarity on the intersection between culture, aesthetic, and capital.

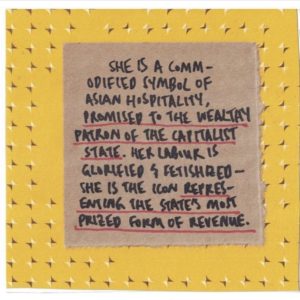

Culture Nation, a creative piece by me

- THE SINGAPORE GIRL: SHE IS A COMMODIFIED SYMBOL OF ASIAN HOSPITALITY, PROMISED TO THE WEALTHY PATRON OF THE CAPITALIST STATE. HER LABOUR IS GLORIFIED & FETISHISED—SHE IS THE ICON REPRESENTING THE STATE’S MOST PRIZED FORM OF REVENUE.

- THE BOUGAINVILLEA: THE BOUGAINVILLEA IS PROOF OF A CITY THAT HAS BEEN METICULOUSLY PLANNED—IT COLOURS OUR INFRASTRUCTURE AND FUNCTIONS AS A SYMBOL OF CLASS & ORDER. THE FOREIGN VISITOR IS IMPRESSED.

Decentering power means centering affect. It means celebrating that we don’t always know, and that opening ourselves up to visceral emotion can get us to the root of knowing in ways that are much more meaningful than dense philosophy. Capitalism has us in a binding arrangement with creating ‘value’, which is to say only we should create if our creations can bear price tags, patents, profits; if it will fit into the demand & supply economy. Creation isn’t so much an alternative paradigm as it is one that has been devalued and hidden. For migrant workers, creating is only allowed to happen on Sundays, in crowded, stuffy dorms on tiny mobile phones that are used to call home—to mark their presence there, and to jot down poems—to mark their presence here. Decentering power means letting creation come first: letting it rejuvenate and regenerate, letting it be big and loud, letting it invent dynamics I cannot even pen here because we have not yet imagined them.

Another aspect of creation that I think is so important is practising solidarity and figuring out what that might look like for us as individuals and as communities. To me, solidarity is:

-

- Mutual aid;

- Anti-racism;

- Calling in and out;

- Listening;

- Creating safe environments for vulnerable groups and communities that have been minoritised to speak up;

- Feminism;

- Being accountable for harm caused and making amends to rebuild trust;

- Holding systems and people in power accountable, where it is safe and possible;

- Using knowledge and unique skills to disrupt, agitate, dismantle oppressive systems;

- Transformative Justice;

- Redistributing power, resources, wealth;

- Creating alternative avenues of knowledge production that are centred around minority voices;

- Communal activities like cooking, childcare, carpooling, farming etc.;

- Using pre-existing cultural practises to build solidarity networks; and

- Invisible and visible demonstrations.

For you, solidarity might mean so much else.

Solidarity and allyship are terms that are peddled a lot in the language of social justice, but they are more than just vocabulary: they are ‘doing words’. Solidarity is an ongoing, conscious practise that I believe can truly change the way we relate to one another, and generate new ways of living and breathing outside of the imperialist, capitalist democracy.

I want to end with an excerpt from Feminism, Interrupted by Lola Olufemi which is one of the most accessible, transformative books I have had the privilege of reading. I recommend it to anyone who seeks a deeper understanding of radical feminism (i.e. not neoliberal, not binary) and the power it has to dramatically change the world. A feminst definition might understand solidarity as a strategic coalition of individuals who are invested in a collective vision of the future. At the core of solidarity is mutual aid: the idea that we give our platforms, resources, legitimacy, voices, skills to one another to try and defeat oppressive conditions. We give and take from one another, we become accomplices and saboteurs and disrupters on each other’s behalf.

A feminst definition might understand solidarity as a strategic coalition of individuals who are invested in a collective vision of the future. At the core of solidarity is mutual aid: the idea that we give our platforms, resources, legitimacy, voices, skills to one another to try and defeat oppressive conditions. We give and take from one another, we become accomplices and saboteurs and disrupters on each other’s behalf.

[…]

But as long as we live under the conditions that we do, solidarity is one of the most important political tools we can use to maximise our success and make demands that cut across the structural barriers that seek to individualise our experiences.

Lola Olufemi, Feminism, Interrupted

The Labourer, by Monir Ahmod (Shromik)

Translated by Gopika Jadeka and Debobrata Basu

Craftsman of this beautiful civilisation

the touch of your sweet has been erased

from the bricks of these mansions

Layers of damp cement

colour the courtyard and your image

will never surface in the cities crafted

like weaver birds’ nests

In this empire of pleasure

you will live in the dense loveless forest

with your inherited hunger

no one knows that you also have

Love

dreams within dreams

The spirits of the moon-lit night shed

the perfume of the heart on your body

smelling of sweat

Craftsmen, after adorning the heart of the earth

one day you will lie in eternal sleep

Like Aminul, perhaps you will become

an unclaimed corpse by the lake

Maybe like Ruhul Amin, your dead body

will lose the right to touch the soil of your land

for the crime of being a migrant

Drowning in the brick and mortar of Rana Plaza

burning in the fire of Tazreen

maybe you will disappear from the earth

Ignoring your sweat and blood

the earth will shine in rainbow colours

On an earth without your grave

On a page in the diary of a heaven dweller

you will be a history, an unread history